In ancient Greek and Sanskrit (Indian) writings dating back to 2000 BC, recommendations of water treatment methods are seen. Ancient peoples knew that heating water might purify it, and were additionally educated in sand and gravel filtration, boiling, and straining. The major motive for water purification was to improve the taste of drinking water, because people could not yet pinpoint the imperceptible distinctions between foul and clean water. Turbidity was the main driving force for the earliest water treatments. Not much was yet known about microorganisms or chemical contaminants.

After 1500 BC, the Egyptians first discovered the principle of coagulation, for which they applied chemical alum for suspended particle settlement. Pictures of this purification technique were found on the wall of the tomb of Amenophis II and Ramses II.

After 500 BC, Hippocrates discovered the healing powers of water. He invented the practice of sieving water and obtained the first bag filter, which was called the ‘Hippocratic sleeve’. The main purpose of the bag was to correct aesthetic issues by trapping sediments that caused bad tastes or odours.

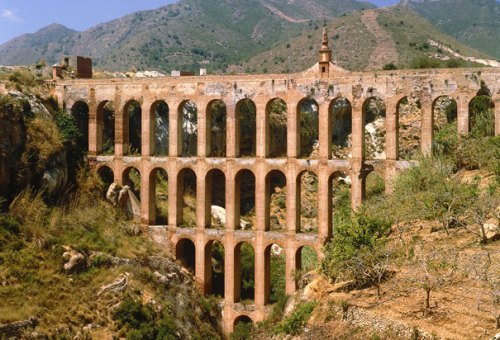

In 300-200 BC, Rome built its first aqueducts, and Archimedes invented his water screw. During the Middle Ages (500-1500 AD), the water supplies regressed in sophistication. These centuries where also known as the Dark Ages, because of a lack of scientific innovations and experiments. After the fall of the Roman Empire, enemy forces destroyed many aqueducts and disallowed the construction of new ones. The future for water treatment was uncertain.

Then in 1627, water-treatment advancement rebooted as Sir Francis Bacon started experimenting with seawater desalination. He attempted to remove salt particles by means of an unsophisticated form of sand filtration. Although unavailing for the most part, the move did pave the way for further experimentation by other scientists.

Experimentation by two Dutch spectacle-makers with object magnification led to the discovery of the microscope by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in the 1670s. He grinded and polished lenses to achieve greater magnification. The invention enabled scientists to observe tiny particles in water; and in 1676, Van Leeuwenhoek caught a first glimpse at water microorganisms.

In the 1700s the first water filters for domestic application were manufactured from wool, sponge and charcoal. In 1804, the first actual municipal water treatment plant was designed by Robert Thom and erected in Scotland. Water treatment was based on slow sand filtration, and was distributed to consumers by horse-and-cart. Some three years later, the first water pipes were installed. The suggestion was made that every person should have access to safe drinking water, but it would take somewhat longer before this was actually brought to practice in most countries.

In 1854 it was discovered that the cholera epidemic was spread through water, since outbreaks seemed less severe in areas where sand filters were installed. British scientist John Snow found that the direct cause of the outbreak was water pump contamination by sewage water. He applied chlorine to purify the water, thus paving the way for modern water disinfection standards. Since the water in the pump had no odd taste or odour, the conclusion was finally drawn that good taste and smell alone do not guarantee safe drinking water. This discovery led to governments starting to install municipal water filters (sand filters and chlorination), which became the first instance of government regulation of public water.

In the 1890s, America started building large sand filters to protect public health, which turned out to be a success. Rapid sand filtration replaced slow sand filtration, and filter capacity was improved by periodic cleanings with powerful jet steam. Subsequently, Dr. Fuller found that rapid sand filtration worked much better when it was preceded by coagulation and sedimentation techniques. Meanwhile, such waterborne illnesses as cholera and typhoid became less and less common as water chlorination won terrain throughout the world.

However, the victory obtained by the invention of chlorination did not last long. After some time, the negative effects of this element were discovered. Chlorine vaporizes much faster than water, and was therefore linked to the aggravation and cause of respiratory disease. Water experts started looking for alternative water disinfectants. In 1902, calcium hypochlorite and ferric chloride were mixed in a drinking water supply in Belgium, resulting in both coagulation and disinfection. In 1906, ozone was first applied as a disinfectant in France. Additionally, people started installing home water filters and shower filters to prevent negative effects of chlorine in water.

In 1903, water softening was invented as a technique for water desalination. Cations were removed from water by exchanging them with sodium or other cations, through the process of ion exchange.

Eventually, starting in 1914, drinking water standards were implemented for drinking water supplies in public traffic based on coliform growth. It would take until the 1940s before drinking water standards applied to municipal drinking water. In 1972, the Clean Water Act was passed in the United States; and in 1974, the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) was formulated. The general principle in the developed world was now that every person had the right to safe drinking water.

Starting in 1970, public health concerns shifted from waterborne illnesses caused by disease-causing microorganisms, to anthropogenic water pollution, such as pesticide residues, industrial sludge and organic chemicals. Regulations now focused on industrial waste and industrial water contamination, and water treatment plants were adapted. Techniques such as aeration, flocculation, and active carbon adsorption were applied. In the 1980s, membrane development for reverse osmosis was added to the list. Risk assessments were enabled after 1990.

Water treatment experimentation today focuses mainly on disinfection by-products. An example is the formation of trihalomethane (THM) from chlorine disinfection, which are organics linked to cancer. Lead also became a concern after it was discovered to corrode from water pipes due to the high pH of disinfected water. Today, lead pipes in water distribution networks are replaced with corrosion-resistant components, and engineers continue to innovate their water system designs as new discoveries emerge.